![]()

FACET SYNDROME AND THE RELIEF OF LOW BACK PAIN

Introduction

The lumbar facet joints were first suggested to be a major source of back pain and sciatica in 1911. The role of the lumbar facet joints is now well described in the literature and has an estimated incidence of between 15-21% of nonspecific low back pain. It's interest as a site of pain has waxed and waned over the last 40 years for two reasons. The first has been the preoccupation of surgeons since 1934 with the lumbar disc as the primary determinant of low back pain. The second has been the lack of correlation between symptoms and X-ray imaging. It has only been after the realization that lumbar disc surgery has only limited success and is not a comprehensive treatment for all back pain that the lumbar facets have seen a resurgence as a significant treatable cause of low back pain and disability. However, it wasn't until 1971, when Rees proposed surgical denervation of the facet joint by percutaneous rhizotomy, that interest in "facet syndrome" was peaked. This interest was further bolstered in 1976 when Mooney and Robertson confirmed the entity by intra-articular injections of hypertonic saline in volunteers to reproduce the symptoms felt by many chronic back pain sufferers.

Clinical Presentation

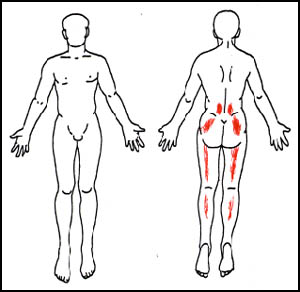

- Unfortunately there are no clinical or laboratory test to definitively diagnose facet syndrome. The mere presence of morphological changes in the joints on imaging studies does not necessarily implicate the joint as the cause for pain. Therefore, the diagnosis of facet syndrome relies exclusively on the results of radiographically confirmed diagnostic anesthetic blocks. Studies have confirmed that the pattern of pain is unreliable in the diagnosis of facet syndrome , , however, below is a typical pain drawing for patients with pain of facet origin. This pain drawing could be easily misinterpreted as typical sciatica or other known causes of low back There is considerable variation in symptoms between patients, however the features most commonly associated with the syndrome include:

- Tenderness localized over one or more facet joints,

- Diffuse referred pain over the buttock and sometimes posterolateral thigh,

- Exacerbation of pain with any sustained posture,

- Loss of lumbar lordosis, or paraspinous muscle spasm

- Exacerbation of pain with hyperextension.

Anatomy & Pathophysiology

The normal function of the vertebral facet joints is to resist axial rotation or torsion of the intervertebral joint and protect the disc from annular tears. The articular facets, upon lumbar flexion, resist saggital translation (forward shear) by direct impaction of the articular surfaces. Normally the facet joints do not have a weight bearing function, but with disc space narrowing, as with aging and disc disease, the joint may be required to bear as much as 70% of the axial compressive forces. Facet joint pain is believed to emanate from the synovial membrane in the joint capsule resulting from repeated stretching, strain or subluxation of the joints with impingement of nonarticular bony surfaces around the joint.

Nerve supply to the facet joints has been a matter of controversy and the source of much of the disagreement regarding the techniques for definitive treatment. The nerve supply originates from the medial branches of the posterior primary rami of the spinal nerves. The nerve curves around the medial end of the transverse process in a groove formed by the junction of the transverse with the root of the superior articular facet. Articular branches are given off to the zygoapophysial joints both above and below the nerve. The anatomy differs at the L5 level in that the L5 dorsal ramus itself, rather than its medial branch crosses the ala of the sacrum at its junction with the superior articular process of the sacrum.

Diagnosis & Treatment

As stated previously, the diagnosis of lumbar facet syndrome is entirely dependent upon the results of radiographically guided lumbar facet blocks. This procedure can be performed by either 1) Intra-articular local anesthetic infiltration or, 2) Medial nerve branch blocks. The specificity of both procedures is entirely dependent upon the experience of the operator and the incidence of false positive results is not known. Several studies bear out the predictive value of diagnostic facet blocks and advocate its use prior to radiofrequency facet denervations.

Intra-articular blocks have the advantage of adding corticosteroids which may reduce or abolish the inflammatory response. Medial nerve blocks have the advantage of being prognostic of the results attainable with radiofrequency denervation.

Conservative treatment consists of physical therapy to "unload" the facet joints and other physical modalities for pain relief, however the response to treatment is limited or inconsistent, several studies have confirmed the benefit of radiofrequency lumbar facet denervations. Several advancements have been made in the technique which have increased its' safety and effectiveness. New 22 gauge disposable electrodes have been developed which have greatly enhanced patient comfort by allowing the physician to anesthetize and ablate the nerve through a single needle. In addition the targeting approach for lesioning has recently been modified to take into account the physical spread of the current to maximize the "burn" area. These modification have increased the likelihood of a successful denervation with confirmed long term success rates between 35-76% in patients treated with this procedure.